Tracking Changes

Last updated on 2024-03-12 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do I record changes in Git?

- How do I check the status of my version control repository?

- How do I record notes about what changes I made and why?

Objectives

- Go through the modify-add-commit cycle for one or more files.

- Explain where information is stored at each stage of that cycle.

- Distinguish between descriptive and non-descriptive commit messages.

First let’s make sure we’re still in the right directory. You should be in the planets directory.

BASH

cd ~/Desktop/planetsCreate and edit a new file

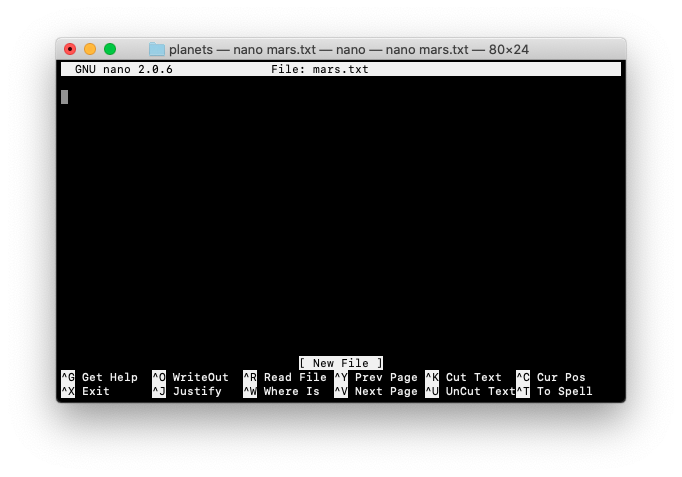

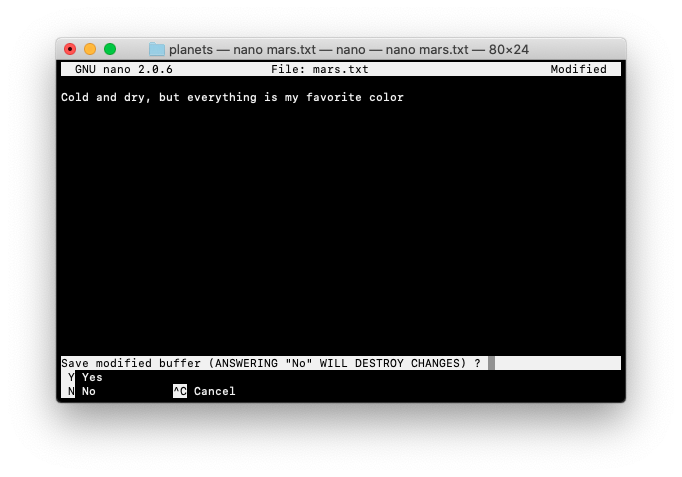

Let’s create a file called mars.txt that contains some notes about the Red Planet’s suitability as a base. We’ll use nano to edit the file; you can use whatever editor you like. In particular, this does not have to be the core.editor you set globally earlier. But remember, the bash command to create or edit a new file will depend on the editor you choose (it might not be nano). For a refresher on text editors, check out “Which Editor?” in The Unix Shell lesson.

BASH

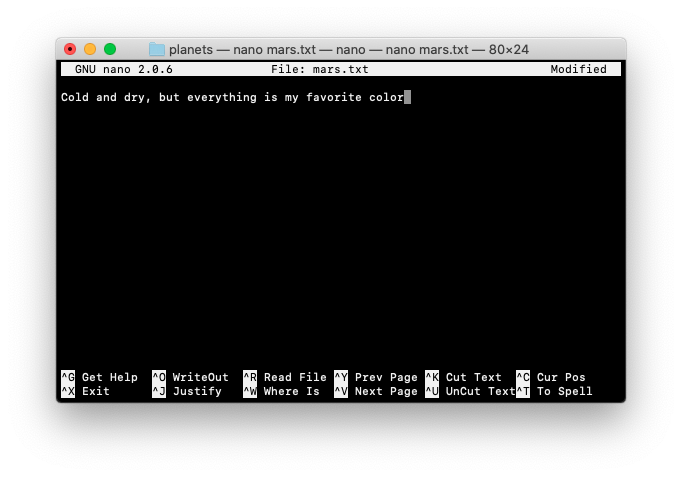

nano mars.txtType the text below into the mars.txt file:

OUTPUT

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite colorLet’s first verify that the file was properly created by running the list command (ls):

BASH

lsOUTPUT

mars.txtmars.txt contains a single line, which we can see by running:

BASH

cat mars.txtOUTPUT

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite colorCheck status

If we check the status of our project again, Git tells us that it’s noticed the new file:

BASH

git statusOUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

mars.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The “untracked files” message means that there’s a file in the directory that Git isn’t keeping track of.

git add

We can tell Git to track a file using git add:

BASH

git add mars.txtand then check that the right thing happened:

BASH

git statusOUTPUT

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: mars.txt

git commit

Git now knows that it’s supposed to keep track of mars.txt, but it hasn’t recorded these changes as a commit yet. To get it to do that, we need to run one more command:

BASH

git commit -m "Start notes on Mars as a base"OUTPUT

[main (root-commit) f22b25e] Start notes on Mars as a base

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 mars.txtWhen we run git commit, Git takes everything we have told it to save by using git add and stores a copy permanently inside the special .git directory. This permanent copy is called a commit (or revision) and its short identifier is f22b25e. Your commit may have another identifier.

We use the -m flag (for “message”) to record a short, descriptive, and specific comment that will help us remember later on what we did and why. If we just run git commit without the -m option, Git will launch nano (or whatever other editor we configured as core.editor) so that we can write a longer message.

Good commit messages start with a brief (<50 characters) statement about the changes made in the commit. Generally, the message should complete the sentence “If applied, this commit will”

If we run git status now:

BASH

git statusOUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working directory cleanit tells us everything is up to date.

git log and git diff

If we want to know what we’ve done recently, we can ask Git to show us the project’s history using git log:

BASH

git logOUTPUT

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Start notes on Mars as a basegit log lists all commits made to a repository in reverse chronological order. The listing for each commit includes the commit’s full identifier (which starts with the same characters as the short identifier printed by the git commit command earlier), the commit’s author, when it was created, and the log message Git was given when the commit was created.

Where Are My Changes?

If we run ls at this point, we will still see just one file called mars.txt. That’s because Git saves information about files’ history in the special .git directory mentioned earlier so that our filesystem doesn’t become cluttered (and so that we can’t accidentally edit or delete an old version).

Now suppose Dracula adds more information to the file. (Again, we’ll edit with nano and then cat the file to show its contents; you may use a different editor, and don’t need to cat.)

We can see our new text in the mars.txt file

BASH

nano mars.txt

cat mars.txtOUTPUT

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for WolfmanWhen we run git status now, it tells us that a file it already knows about has been modified:

BASH

git statusOUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")The last line is the key phrase: “no changes added to commit”. We have changed this file, but we haven’t told Git we will want to save those changes (which we do with git add) nor have we saved them (which we do with git commit). So let’s do that now. It is good practice to always review our changes before saving them. We do this using git diff. This shows us the differences between the current state of the file and the most recently saved version:

BASH

git diffOUTPUT

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index df0654a..315bf3a 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

+The two moons may be a problem for WolfmanThe output is cryptic because it is actually a series of commands for tools like editors and patch telling them how to reconstruct one file given the other. If we break it down into pieces:

- The first line tells us that Git is producing output similar to the Unix

diffcommand comparing the old and new versions of the file. - The second line tells exactly which versions of the file Git is comparing;

df0654aand315bf3aare unique computer-generated labels for those versions. - The third and fourth lines once again show the name of the file being changed.

- The remaining lines are the most interesting, they show us the actual differences and the lines on which they occur. In particular, the

+marker in the first column shows where we added a line.

After reviewing our change, it’s time to commit it:

BASH

git commit -m "Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman"OUTPUT

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: mars.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Whoops: Git won’t commit because we didn’t use git add first. Let’s fix that:

BASH

git add mars.txt

git commit -m "Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman"OUTPUT

[main 34961b1] Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)Git insists that we add files to the set we want to commit before actually committing anything. This allows us to commit our changes in stages and capture changes in logical portions rather than only large batches. For example, suppose we’re adding a few citations to relevant research to our thesis. We might want to commit those additions, and the corresponding bibliography entries, but not commit some of our work drafting the conclusion (which we haven’t finished yet).

To allow for this, Git has a special staging area where it keeps track of things that have been added to the current changeset but not yet committed.

Staging Area

If you think of Git as taking snapshots of changes over the life of a project, git add specifies what will go in a snapshot (putting things in the staging area), and git commit then actually takes the snapshot, and makes a permanent record of it (as a commit). If you don’t have anything staged when you type git commit, Git will prompt you to use git commit -a or git commit --all, which is kind of like gathering everyone to take a group photo! However, it’s almost always better to explicitly add things to the staging area, because you might commit changes you forgot you made. (Going back to the group photo simile, you might get an extra with incomplete makeup walking on the stage for the picture because you used -a!) Try to stage things manually, or you might find yourself searching for “git undo commit” more than you would like!

Let’s watch as our changes to a file move from our editor to the staging area and into long-term storage. First, we’ll add another line to the file:

BASH

nano mars.txt

cat mars.txtOUTPUT

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidityBASH

git diffOUTPUT

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humiditySo far, so good: we’ve added one line to the end of the file (shown with a + in the first column). Now let’s put that change in the staging area and see what git diff reports:

BASH

git add mars.txt

git diffThere is no output: as far as Git can tell, there’s no difference between what it’s been asked to save permanently and what’s currently in the directory. However, if we do this:

BASH

git diff --stagedOUTPUT

diff --git a/mars.txt b/mars.txt

index 315bf3a..b36abfd 100644

--- a/mars.txt

+++ b/mars.txt

@@ -1,2 +1,3 @@

Cold and dry, but everything is my favorite color

The two moons may be a problem for Wolfman

+But the Mummy will appreciate the lack of humidityit shows us the difference between the last committed change and what’s in the staging area. Let’s save our changes:

git commit -m "Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy"OUTPUT

[main 005937f] Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)check our status:

git statusOUTPUT

On branch main

nothing to commit, working directory cleanand look at the history of what we’ve done so far:

git logOUTPUT

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5 (HEAD -> main)

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

commit 34961b159c27df3b475cfe4415d94a6d1fcd064d

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:07:21 2013 -0400

Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

commit f22b25e3233b4645dabd0d81e651fe074bd8e73b

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 09:51:46 2013 -0400

Start notes on Mars as a basePaging the Log

When the output of git log is too long to fit in your screen, git uses a program to split it into pages of the size of your screen. When this “pager” is called, you will notice that the last line in your screen is a :, instead of your usual prompt.

- To get out of the pager, press Q.

- To move to the next page, press Spacebar.

- To search for

some_wordin all pages, press / and typesome_word. Navigate through matches pressing N.

Limit Log Size

To avoid having git log cover your entire terminal screen, you can limit the number of commits that Git lists by using -N, where N is the number of commits that you want to view. For example, if you only want information from the last commit you can use:

BASH

git log -1OUTPUT

commit 005937fbe2a98fb83f0ade869025dc2636b4dad5 (HEAD -main)

Author: Vlad Dracula <vlad@tran.sylvan.ia>

Date: Thu Aug 22 10:14:07 2013 -0400

Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for MummyYou can also reduce the quantity of information using the --oneline option:

BASH

git log --onelineOUTPUT

005937f (HEAD -> main) Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

34961b1 Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

f22b25e Start notes on Mars as a baseYou can also combine the --oneline option with others. One useful combination adds --graph to display the commit history as a text-based graph and to indicate which commits are associated with the current HEAD, the current branch main, or other Git references:

BASH

git log --oneline --graphOUTPUT

* 005937f (HEAD -> main) Discuss concerns about Mars' climate for Mummy

* 34961b1 Add concerns about effects of Mars' moons on Wolfman

* f22b25e Start notes on Mars as a baseExercises

Directories

Two important facts you should know about directories in Git.

1. Git does not track directories on their own, only files within them.

Try it for yourself:

BASH

mkdir spaceships

git status

git add spaceships

git statusNote, our newly created empty directory spaceships does not appear in the list of untracked files even if we explicitly add it (via git add) to our repository. This is the reason why you will sometimes see .gitkeep files in otherwise empty directories. Unlike .gitignore, these files are not special and their sole purpose is to populate a directory so that Git adds it to the repository. In fact, you can name such files anything you like.

2. If you create a directory in your Git repository and populate it with files, you can add all files in the directory at once by

BASH

git add <directory-with-files>Try it for yourself:

BASH

touch spaceships/apollo-11 spaceships/sputnik-1

git status

git add spaceships

git statusBefore moving on, we will commit these changes.

BASH

git commit -m "Add some initial thoughts on spaceships"To recap, when we want to add changes to our repository, we first need to add the changed files to the staging area (git add) and then commit the staged changes to the repository (git commit):

Answer 1 is not descriptive enough, and the purpose of the commit is unclear; and answer 2 is redundant to using “git diff” to see what changed in this commit; but answer 3 is good: short, descriptive, and imperative.

Committing Changes to Git

Which command(s) below would save the changes of myfile.txt to my local Git repository?

Option 1git commit -m "my recent changes"

Option 2git init myfile.txt git commit -m "my recent changes

Option 3git add myfile.txt git commit -m "my recent changes"

Option 4git commit -m myfile.txt "my recent changes"

- Would only create a commit if files have already been staged.

- Would try to create a new repository.

- Is correct: first add the file to the staging area, then commit.

- Would try to commit a file “my recent changes” with the message myfile.txt.

Committing Multiple Files

The staging area can hold changes from any number of files that you want to commit as a single snapshot.

- Add some text to

mars.txtnoting your decision to consider Venus as a base - Create a new file

venus.txtwith your initial thoughts about Venus as a base for you and your friends - Add changes from both files to the staging area, and commit those changes.

The output below from cat mars.txt reflects only content added during this exercise. Your output may vary. First we make our changes to the mars.txt and venus.txt files:

BASH

nano mars.txt

cat mars.txtOUTPUT

Maybe I should start with a base on Venus.BASH

nano venus.txt

cat venus.txtOUTPUT

Venus is a nice planet and I definitely should consider it as a base.Now you can add both files to the staging area. We can do that in one line:

BASH

git add mars.txt venus.txtOr with multiple commands:

BASH

git add mars.txt

git add venus.txtNow the files are ready to commit. You can check that using git status. If you are ready to commit use:

BASH

git commit -m "Write plans to start a base on Venus"OUTPUT

[main cc127c2]

Write plans to start a base on Venus

2 files changed, 2 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 venus.txtKey Points

-

git statusshows the status of a repository. - Files can be stored in a project’s working directory (which users see), the staging area (where the next commit is being built up) and the local repository (where commits are permanently recorded).

-

git addputs files in the staging area. -

git commitsaves the staged content as a new commit in the local repository. - Write a commit message that accurately describes your changes.